- Home

- Danielle Paige

No Place Like Oz

No Place Like Oz Read online

Dedication

Thanks to Angela and Darren Croucher for all their help

Contents

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Excerpt from Dorothy Must Die

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

One

They say you can’t go home again. I’m not entirely sure who said that, but it’s something they say. I know it because my aunt Em has it embroidered on a throw pillow in the sitting room.

You can’t go home again. Well, even if they put it on a pillow, whoever said it was wrong. I’m proof alone that it’s not true.

Because, you see, I left home. And I came back. Lickety-split, knock your heels together, and there you are. Oh, it wasn’t quite so simple, of course, but look at me now: I’m still here, same as before, and it’s just as if I was never gone in the first place.

So every time I see that little pillow on Aunt Em’s good sofa, with its pretty pink piping around the edges and colorful bouquets of daisies and wildflowers stitched alongside those cheerful words (but are they even cheerful? I sometimes wonder), I’m halfway tempted to laugh. When I consider everything that’s happened! A certain sort of person might say that it’s ironic.

Not that I’m that sort of person. This is Kansas, and we Kansans don’t put much truck in anything as foolish as irony.

Things we do put truck in:

Hard work.

Practicality.

Gumption.

Crop yields and healthy livestock and mild winters. Things you can touch and feel and see with your own two eyes. Things that do you at least two licks of good.

Because this is the prairie, and the prairie is no place for daydreaming. All that matters out here is what gets you through the winter. A Kansas winter will grind a dreamer right up and feed it to the pigs.

As my uncle Henry always says: You can’t trade a boatload of wishes for a bucket of slop. (Maybe I should embroider that on a pillow for Aunt Em, too. I wonder if it would make her laugh.)

I don’t know about wishes, but a bucket of slop was exactly what I had in my hand on the afternoon of my sixteenth birthday, a day in September with a chill already in the air, as I made my way across the field, away from the shed and the farmhouse toward the pigpen.

It was feeding time, and the pigs knew it. Even from fifty feet away, I could already hear them—Jeannie and Ezekiel and Bertha—squealing and snorting in anticipation of their next meal.

“Well, really!” I said to myself. “Who in the world could get so excited about a bit of slop!?”

As I said it, my old friend Miss Millicent poked her little red face out from a gap of wire in the chicken coop and squawked in greeting. “And hello to you, too, Miss Millicent,” I said cheerily. “Don’t you worry. You’ll be getting your own food soon enough.”

But Miss Millicent was looking for companionship, not food, and she squeezed herself out of her coop and began to follow on my heels as I kept on my way. I had been ignoring her lately, and the old red hen was starting to be cross about it, a feeling she expressed today by squawking loudly and shadowing my every step, fluttering her wings and fussing underfoot.

She meant well enough, surely, but when I felt her hard beak nipping at my ankle, I finally snapped at her. “Miss Millie! You get out of here. I have chores to do! We’ll have a nice, long heart-to-heart later, I promise.”

The chicken clucked reproachfully and darted ahead, stopping in her tracks just in the spot where I was about to set my foot down. It was like she wanted me to know that I couldn’t get away from her that easily—that I was going to pay her some mind whether I liked it or not.

Sometimes that chicken could be impossible. And without even really meaning to, I kicked at her. “Shoo!”

Miss Millie jumped aside just before my foot connected, and I felt myself lose my balance as I missed her, stumbling backward with a yelp and landing on my rear end in the grass.

I looked down at myself in horror and saw my dress covered in pig slop. My knee was scraped, I had dirt all over my hands, and my slop bucket was upturned at my side.

“Millie!” I screeched. “See what you’ve done? You’ve ruined everything!” I swatted at her again, this time even more angrily than when I’d kicked her, but she just stepped nimbly aside and stood there, looking at me like she just didn’t know what to do with me anymore.

“Oh dear,” I said, sighing. “I didn’t mean to yell at you. Come here, you silly hen.”

Millie bobbled her head up and down like she was considering the proposition before she hopped right into my lap, where she burrowed in and clucked softly as I ruffled her feathers. This was all she had wanted in the first place. To be my friend.

It used to be that it was all I wanted, too. It used to be that Miss Millicent and even Jeannie the pig were some of my favorite people in the world. Back then, I didn’t care a bit that a pig and a chicken hardly qualified as people at all.

They were there for me when I was sad, or when something was funny, or when I just needed company, and that was what mattered. Even though Millie couldn’t talk, it always felt like she understood everything I said. Sometimes it even almost seemed like she was talking to me, giving me her sensible, no-nonsense advice in a raspy cackle. “Don’t you worry, dearie,” she’d say. “There’s no problem in this whole world that can’t be fixed with a little spit and elbow grease.”

But lately, things hadn’t been quite the same between me and my chicken. Lately, I had found myself becoming more impatient with her infuriating cackling, with the way she was always pecking and worrying after me.

“I’m sorry, Miss Millicent,” I said. “I know I haven’t been myself lately. I promise I’ll be back to normal soon.”

She fluffed her wings and puffed her chest out, and I looked around: at the dusty, gray-green fields merging on the horizon with the almost-matching gray-blue sky, and all of it stretching out so far into nothing that it seemed like it would be possible to travel and travel and travel—just set off in a straight line heading east or west, north or south, it didn’t matter—and never get anywhere at all.

“Sometimes I wonder if this is what the rest of life’s going to be like,” I said. “Gray fields and gray skies and buckets of slop. The world’s a big place, Miss Millicent—just look at that sky. So why does it feel so small from where we’re sitting? I’ll tell you one thing. If I ever get the chance to go somewhere else again, I’m going to stay there.”

I felt a bit ashamed of myself. I knew how I sounded.

“Get yourself together and stop moping, Little Miss Fancy,” I responded to myself, now in my raspy, stern, Miss Millicent voice, imagining that the words were coming out of her mouth instead of my own. “A prairie girl doesn’t worry her pretty little head about places she’ll never go and things she’ll never see. A prairie girl worries about the here and now.”

This is what a place like this does to you. It makes you put words in the beaks of chickens.

I sighed and shrugged anyway. Miss Millie didn’t know there was anything else out there. She just knew her coop, her feed, and me.

These days, I envied her for that. Because I was a girl, not a chicken, and I knew what was out there.

Past the prairie, where I sat with my old chicken in my lap, there were ocea

ns and more oceans. Beyond those were deserts and pyramids and jungles and mountains and glittering palaces. I had heard about all those places and all those things from newsreels and newspapers.

And even if I was the only one who knew it, I’d seen with my own eyes that there were more directions to move in than just north and south and east and west, places more incredible than Paris and Los Angeles, more exotic than Kathmandu and Shanghai, even. There were whole worlds out there that weren’t on any map, and things that you would never believe.

I didn’t need to believe. I knew. I just sometimes wished I didn’t.

I thought of Jeannie and Ezekiel and Bertha, all of them in their pen beside themselves in excitement for the same slop they’d had yesterday and would have again tomorrow. The slop I’d have to refill into the bucket and haul back out to them.

“It must be nice not to know any better,” I said to Miss Millicent.

In the end, a chicken is a good thing to hold in your lap for a few minutes. It’s a good thing to pretend to talk to when there’s no one else around. But in the end, if you want the honest-to-goodness truth, it’s possible that a chicken doesn’t make the greatest friend.

Setting Miss Millicent aside, I dusted myself off and headed back toward the farmhouse to clean myself up, change my dress, and get myself ready for my big party. Bertha and Jeannie and Ezekiel would have to wait until tomorrow for their slop.

It wasn’t like me to let them go hungry. At least, it wasn’t like the old me.

But the old me was getting older by the second. It had been two years since the tornado. Two years since I’d gone away. Since I had met Glinda the Good Witch, and the Lion, the Tin Woodman, and the Scarecrow. Since I had traveled the Road of Yellow Brick and defeated the Wicked Witch of the West. In Oz, I had been a hero. I could have stayed. But I hadn’t. Aunt Em and Uncle Henry were in Kansas. Home was in Kansas. It had been my decision and mine alone.

Well, I had made my choice, and like any good Kansas girl, I would live with it. I would pick up my chin, put on a smile, and be on my way.

The animals could just go hungry for now. It was my birthday, after all.

Two

“Happy Swoot Sixtoon,” the cake said, the letters spelled out in smudged icing. I beamed up at my aunt Em with my brightest smile.

“It’s beautiful,” I said. I’d already changed into my party dress—which wasn’t that much different from the dress I’d just gotten all dirty in the field—and had cleaned myself up as best as I could, scrubbing the dirt from my hands and the blood from my knee until you could hardly tell I’d fallen.

Uncle Henry hovered off to the side, looking as proud and hopeful as if he’d baked it himself. He’d certainly helped, gathering the ingredients from around the farm: coaxing the eggs from Miss Millicent (who never seemed in the mood to lay any), milking the cow, and making sure Aunt Em had everything she needed.

“Sometimes I wonder if I didn’t marry a master chef!” Henry said, putting his arm around her waist.

Even Toto was excited. He was hopping around on the floor yipping at us eagerly.

“You really like it?” Aunt Em asked, a note of doubt in her voice. “I know the writing isn’t perfect, but penmanship has never been my strong suit.”

“It’s wonderful!” I exclaimed, pushing down the tiny feeling of disappointment that was bubbling in my chest. A little white lie never hurt anyone, and I didn’t doubt the cake would be delicious. Aunt Em’s food might not usually come out looking fancy, but it always tastes better than anything else.

Oh, I know that it’s how a cake tastes that matters. I know there’s no point in concerning yourself with what it looks like on the outside when you’ll be eating it in just a few minutes.

But as it sat lopsided on the table with its brown icing and the words “Happy Sweet Sixteen” written out so the e’s looked more like blobby o’s, I found myself wishing for something more.

I just couldn’t let Aunt Em know that. I couldn’t let her have even the smallest hint that anything was wrong. So I wrapped her up in a hug to let her know that it didn’t matter: that even if the cake wasn’t perfect, it was good enough for me. But then something else occurred to me.

“Are you sure it’s big enough?” I asked. “A lot of people are coming.” I had invited everyone from school, not that that was so many people, and everyone from all the neighboring farms, plus the store owners at every shop I’d been to on my last trip into town. I’d invited my best friend, Mitzi Blair, and even awful Suzanna Hellman and her best friend, Marian Stiles, not to mention a reporter from the Carrier who had taken a special interest in my life since the tornado. Plus, Suzanna would be dragging her horrible little sister, Jill, along.

Aunt Em glanced down nervously. “There was going to be another layer, dear, but we were running low on eggs . . . ,” she said, trailing off, her weathered face suddenly rosy with embarrassment.

Uncle Henry came quickly to the rescue. “I just won’t have a second helping,” he said, rubbing his belly, which is not small. “It wouldn’t hurt me to skip a first helping, come to think of it.”

My aunt swatted his arm and chuckled, her worry momentarily gone. All those years of hard Kansas life had taken their toll on her, but when she was around my uncle, her eyes still lit up; when he made a joke, she still laughed a laugh that sounded like it belonged to a girl my age. “You’d eat the whole thing if I let you!” He swiped a bit of frosting with his finger and grinned.

Seeing them together like that, happy and playful and still as much in love as they’d ever been, I felt a swell of affection for them, followed immediately by sadness. I knew that, once upon a time, they had been as young as I was. Aunt Em had wanted to travel the world; Uncle Henry had wanted to set off to California and strike gold. They just hadn’t had the chance to do any of those things.

Instead, they had stayed here, and when I asked them about those days now, they waved away my questions like they were ashamed to admit that they’d ever had dreams at all. To them, our farm was all there was.

Will I be like them, someday? I wondered. Happy with crooked cakes and gray skies and cleaning out the pig trough?

“I’m going to go hang the lanterns outside,” Henry said, walking to the door and reaching for his toolbox. “People expect this place to look nice. After all, they helped build it.”

“Only after you got it started,” Aunt Em reminded him.

After the tornado had swept our house away—with me in it—everyone had figured I was dead. Aunt Em and Uncle Henry had been heartbroken. They’d even started planning my memorial service.

Imagine that! My funeral! Well, sometimes I did imagine it. I imagined my teachers from school all standing up one by one to say what a wonderful student I was, that there was something truly special about me.

I imagined Aunt Em all in black, weeping silently into her handkerchief and Uncle Henry the very picture of stoic grief, only a single tear rolling down his stony face as he helped lower my coffin into an open grave. Yes, I know that without a body there could be no coffin, but this was a fantasy. And it was at that moment in my fantasy that Aunt Em would bolt up, wailing, and would race forward to fling herself in after my corpse, stopped only at the last minute by Tom Furnish and Benjamin Slocombe, two handsome farmhands from the Shiffletts’ farm. Tom and Benjamin would be crying, too, because of course, they both harbored a secret admiration for me.

Well, if one’s going to daydream, one might just as well make it a good one, don’t you suppose?

Of course, I know it’s vain, and petty, and downright spoiled of me to do such a thing as daydream about my own funeral. I know it’s downright wicked to take even the slightest pleasure in imagining the misery of others, especially my poor aunt and uncle, who have so little happiness in their lives as it is.

I try not to be vain and petty and spoiled. I certainly try not to be wicked (after my experiences with Wickedness). But we all have our bad points, don’t we? I migh

t as well admit that those happen to be mine, and I can only hope to make up for them with the good ones.

There was no funeral anyway, so no harm was done. Just the opposite, in fact! When I showed up again a few days after the cyclone—without so much as a scratch on me, sitting by the chicken coop, which had somehow remained undisturbed through everything—people had assumed that my survival was some kind of miracle.

They were wrong. Miracles are not the same as magic.

But whether you want to call it a miracle or something else, every paper from Wichita to Topeka put me on the front page. They threw a parade for me that year, and a few months later I was asked to be the head judge at the annual blueberry pie contest at the Kansas State Fair. Best of all, because I came back from my adventures minus one house, everyone in town pitched in to build us a new one.

That was how we got this new house, to replace the old one that was still back in you-know-where. It was quite a spectacle to behold: it was bigger than any other for miles around, with a second story and a separate bedroom just for me, and even an indoor commode and a jaunty coat of blue paint, though that was just as gray as everything else in Kansas soon enough.

Henry and Em didn’t seem particularly happy about any of it. They were humbled, naturally, that our neighbors had done all this for us, especially seeing as how they had all suffered their losses in the cyclone, some of them bigger than ours. Of course we were grateful.

But when the neighbors had done their work and gone home, my aunt and uncle had examined all the unfamiliar extravagances and had concluded that the old house had suited them just fine.

“An indoor commode!” Aunt Em exclaimed. “It just doesn’t seem decent!”

How silly they were being. Grumbling about the gift that had been so kindly given to us.

On the other hand, I had to admit that even I felt that the new house left a few things to be desired. Nothing could compare to what I had seen while I had been gone. How do you go back to a two-bedroom farmhouse in Kansas when you’ve been in a palace made of emeralds?

Ruler of Beasts

Ruler of Beasts Before the Snow

Before the Snow Dorothy Must Die Novella #7

Dorothy Must Die Novella #7 Dorothy Must Die Novella #2

Dorothy Must Die Novella #2 Dorothy Must Die

Dorothy Must Die Dorothy Must Die Novella #8

Dorothy Must Die Novella #8 No Place Like Oz

No Place Like Oz The Wicked Will Rise

The Wicked Will Rise The Ravens

The Ravens Dorothy Must Die Novella #5

Dorothy Must Die Novella #5 The Wizard Returns

The Wizard Returns The Queen of Oz

The Queen of Oz Queen Rising

Queen Rising dorothy must die 00.4 - heart of tin

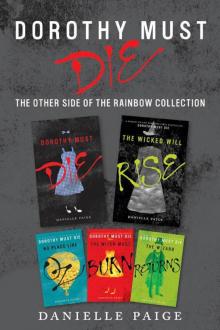

dorothy must die 00.4 - heart of tin Dorothy Must Die: The Other Side of the Rainbow Collection: No Place Like Oz, Dorothy Must Die, The Witch Must Burn, The Wizard Returns, The Wicked Will Rise

Dorothy Must Die: The Other Side of the Rainbow Collection: No Place Like Oz, Dorothy Must Die, The Witch Must Burn, The Wizard Returns, The Wicked Will Rise